Using Data to Advocate For Equitable Infrastructure

by Kiran Herbert, Communications Manager

February 15, 2023

New research from the Spin Mobility Data for Safer Streets Initiative showcases how data can be a powerful tool in making streets safer in underserved communities.

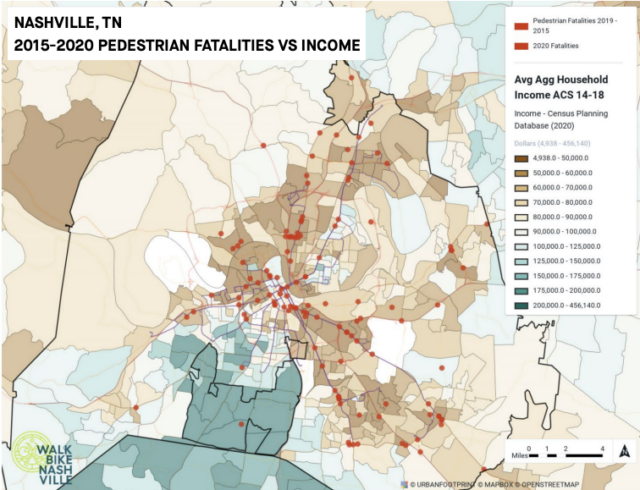

Photo credit: Urban Footprint Analysis complete by Walk Bike Nashville, one of the 2020 grantees in the Spin Mobility Data for Safer Streets Initiative.

It shouldn’t come as a surprise to BBSP readers that large inequities exist in U.S. cities regarding infrastructure, including the bike share and scooter share systems that make up the micromobility landscape. Unfortunately, decades of unfair zoning policies, overtly racist laws, and disinvestment in BIPOC and low-income neighborhoods have exasperated inequity, affecting everything from education and economic outcomes to where buses run and shared micromobility services are located.

There are a lot of emotional stories to be told about how bike fatalities are worse for Black and Hispanic Americans, largely because the infrastructure in Black and Latino neighborhoods is lacking and studies like the ones linked are a crucial part of documenting inequity and sparking change. Data, after all, is what speaks most to legislators and planners and good data around mobility is crucial to informing budgets and policies to combat decades of racist planning. Data is a powerful tool when it comes to building people-first places that prioritize the safety and well-being of everyone.

Recognizing the importance of good data, the scooter and bike share company Spin first launched its Mobility Data for Safer Streets (MDSS) program in 2020. The program awarded advocacy organizations around the country with a unique suite of data sources, software tools, and physical equipment to gather, analyze, understand, and present data for street advocacy. A recently published study, titled “Using Emerging Mobility Data to Advocate Equitable Micromobility Infrastructure in Underserved Communities,” leverages the findings from that program to understand emerging data use cases and applications related to promoting equity in active transportation planning. Notably, it also highlights characteristics of the data tools that are supportive or inhibitive of these purposes.

The MDSS Initiative awarded six nonprofit active transportation organizations across the U.S. access to a suite of six data platforms and tools to support their efforts to make streets safer for active transportation in general, and micromobility specifically.

The 2020 nonprofit awardees:

- BikeWalkNC

- Sustain Charlotte

- Bike Cleveland

- Walk Bike Nashville

- Bike Utah & Bike Walk Provo

- Denver Streets Partnership

The 2020 mobility data tools:

In addition to the mobility data tolls outlined above, grantees were provisioned with three physical data tools: one radar speed gun, one bike-pedestrian counter, and one time-lapse camera. The grant was premised on the idea that in order to create 15-minute cities, better data is needed, and in order to get that data, advocates, researchers, and planners need access to the (often unaffordable) tools to collect and analyze data, helping them make the case for streets that are more sustainable, equitable, and safer for everyone.

Equity was a prevalent theme across advocates’ use of the data tools and the research documents lessons learned from grantees as they leveraged data in their work for and with underrepresented communities to create more better transportation systems. While somewhat dense, the paper identifies equity-related use cases and applications for the mobility data tools and how they either served or didn’t serve particular applications. Overall, the MDSS awardees demonstrated five data tool use cases related to equity, sometimes in combination:

- Characterizing active transportation usage (in terms of who was doing it, where, and what times, and for what reasons)

- Accessibility (proximity and travel times to basic needs)

- Active transportation infrastructure (in terms of where it is located, its type and quality, and how connected it is)

- Safety outcomes (i.e. crashes, injuries, or fatalities) in underserved communities or in relation to sociodemographic variables

- Researching an underserved community in preparation for community engagement activities

The research paper examines each of the above themes in detail, offering specific case studies from the grantees. For example, Bike Utah used StreetLight to look for correlations between cycling volumes and US Census household income and race/ethnicity data, inferring who was cycling based on where cycling was occurring. The organization found that heavy bike riding was occurring in areas with large low-income and Latinx populations. SteetLight was also used to create heatmaps of cycling and pedestrian volumes — the resulting data helped advocates determine that most bicyclists were riding for utility.

In another case study, Walk Bike Nashville used UrbanFootprint for its “Murfreesboro Pike Project,” which sought to understand the mobility gaps and transportation needs of a low-income corridor centered on Murfreesboro Pike, the second busiest transit route in the city and among the most deadly. Advocates at the organization were able to use UrbanFootprint to familiarize themselves with the communities along the Pike and their needs — looking at travel patterns, socioeconomics, languages spoken, and race/ethnicities — before reaching out in engagement efforts.

Likewise, Sustain Charlotte used UrbanFootprint to measure resident accessibility via non-car modes to essential services in the Charlotte “Arc” (the three neighborhoods of North, East, and West Charlotte), BIPOC and low-income communities with major transportation, quality of life, and equity challenges. The tool helped the advocacy organization map for the number of jobs within a 20-minute walk, the travel time to parks, schools, and shops, and the proximity to other basic needs like pharmacies, grocery stores, and banks. The data shows that Arc residents without a car had poor access to basic needs.

The research outlines tons of great use cases, highlighting how data can really help “arm” advocates with information, which in turn can lead to change on the ground. Speaking with researchers, advocates noted how the data tools allowed them to “speak a common language with city planners and local officials.” It also helped them provide underserved communities with tangible stats, maps, and information that they could then use to advocate for their own communities. Overall, the data helped organizations confront biases in the current planning process and better inform, equip, and involve underrepresented communities. Researchers concluded that the data tools helped the six awardees support underserved communities in a way that would not have been possible otherwise.

BIPOC and low-income communities are often not well-represented in planning meetings yet they’re often the communities that suffer the most from mobility gaps or inadequate infrastructure. This study highlights how data tools can help rectify some of the damage done, helping advocates speak the same language as city planners and backing up their arguments with data to influence decision-making and confront ingrained biases. For organizations focusing specifically on shared micromobility, the tools could be used to understand communities ahead of engagement, identify possible station locations or “equity zones” for vehicle placement, or tailor messaging (the possibilities are endless).

Most cities already have these data tools at their disposal but use them to disproportionately focus on vehicle traffic. By providing active transportation advocates with these mobility data resources, Spin has helped make the case for their widespread adoption by those trying to achieve more equitable outcomes (after all, tools are only as good as the person using them). In 2021, Spin awarded another round of MDSS grantees with a slightly different set of mobility tools — we look forward to seeing the results of that work.

The Better Bike Share Partnership is funded by The JPB Foundation as a collaboration between the City of Philadelphia, the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO), and the PeopleForBikes Foundation to build equitable and replicable bike share systems. Follow us on LinkedIn, Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram or sign up for our weekly newsletter. Got a question or a story idea? Email kiran@peopleforbikes.org.