Equity Issues in Cashless Fare Payment

by Kiran Herbert, Communications Manager

August 17, 2022

A new paper explores the challenges facing U.S. transit riders without bank accounts or smartphones, and offers solutions to ensure they’re not left behind.

The Better Bike Share Partnership has long advocated for bike share systems to offer a cash payment option. In the United States, about 10% of US adults lack a bank account or credit card, and many rely on restrictive cellphone data plans or do not have access to the internet or a smartphone. In order to serve these individuals, retaining a cash payment option for bike share specifically and transit, in general, is crucial.

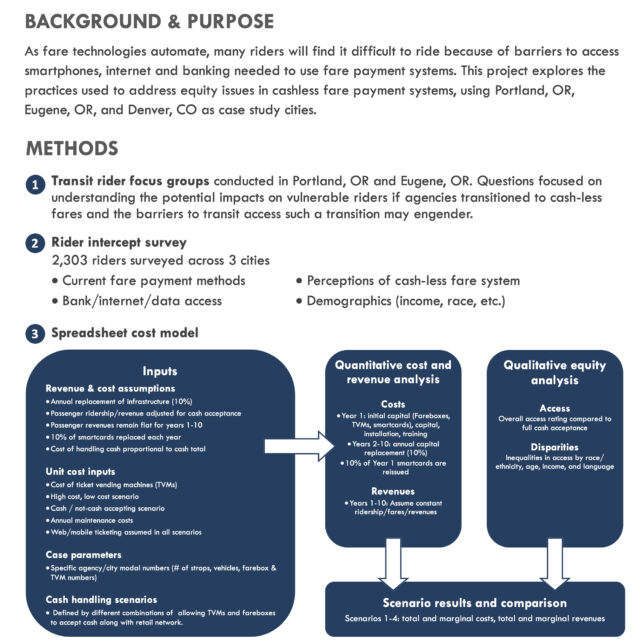

Still, many transit agencies are moving towards completely cashless systems, which have the benefit of lowering operating costs and speeding up boarding times. Cognizant that this transition might exclude some riders and even undermine transit ridership, a consulting firm and several transit agencies approached Portland State University’s Transporation Research and Education Center (TREC) to study the issue and to help chart a course forward. In spring 2019, a study led by Aaron Golub, director and associate professor of urban studies and planning, was underway.

While the study wrapped in 2021 and the final, 91-page report was published shortly thereafter, a new paper tied to that research, titled “Equity and Exclusion Issues in Cashless Fare Payment Systems for Public Transportation,” was released this month and offers a summary of those findings. The paper examines transit users’ experiences with fare technologies using a survey of riders in Denver, Colorado, as well as Portland and Eugene, Oregon. It outlines which riders are most at risk of being excluded, and how mitigation strategies could work to overcome barriers to cashless transit.

“There’s going to be big growing pains around this transition because there’s a significant share of the population that still is underbanked and unbanked,” says Golub, adding that even among the population that does have a credit card and a smartphone, there are folks who don’t know how to use them well enough to link to automated payment systems (like Apple or Google Pay) or download an app. “They’re going to be really struggling — it’s a large group of transit riders, but it’s not everyone.”

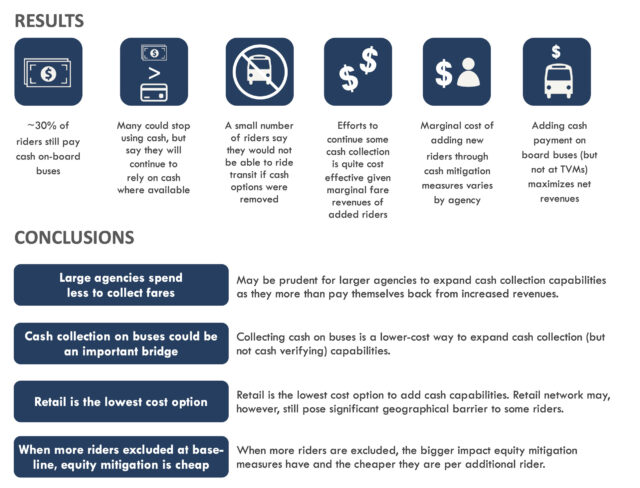

Some 30% of transit riders currently use cash onboard buses. As part of the study, researchers intercepted and interviewed roughly 2,200 transit riders in Denver, Portland, and Eugene. Of those surveyed, many but not all users claim that they would be able to switch and accommodate a cashless system. Older and low-income riders, however, are most at risk of not being able to adapt, as they are more likely to lack access to smartphones or the internet. Notably, many survey respondents (about 30%) that did have smartphones lacked a data plan or (20%) were concerned about reaching cell phone data limits.

There’s an argument to be made that in ten years — the rough sketch used for U.S. systems to go completely cashless — more people will become banked and gain access to the internet and smartphones. Already, we’re seeing major government subsidies for broadband and universal WiFi, although banking rates have remained more stagnant. To solve for those individuals who will still be without smartphones, Golub suggests agencies might simply give out devices.

“To close that gap at the end, maybe there will be free smartphone programs,” says Golub. “The results of this research also suggest that agencies should have free WiFi so that people can use that instead of their data plan.”

In addition to free public WiFi, another potential solution includes incorporating retail workarounds like PayNearMe or Cash App, as MoGo, Detroit’s bike share system, has already started to do. Educational materials and training around how to use new systems, as well as things like downloading apps and setting up automated payment systems, are also needed.

“You can’t just assume people know how to do that,” says Golub. “It’s important to have an affirmative and explicit plan to get those folks trained and up to speed.”

Community outreach has the added benefit of helping build trust amongst a population that is skeptical of having their information tracked or stored. Local conditions and patterns will also differ substantially, and local surveys, focus groups, and responsive solutions are recommended to help create a tailored response to each city’s transition.

Maintaining an office or some machines that accept cash payments is also an option, and many cities and systems have gone that route. Many transit agencies also offer low-income programs that wouldn’t be affected by a cashless transition since recipients are given fare cards that can be refilled with cash at a discount at many retail outlets.

“Like with many programs, it’s not the lowest income earners, it’s the ones just above qualifying that are the worst off,” says Golub.

While not a part of the academic paper, the larger TREC report weighs the costs and benefits of keeping some cash payment options versus going completely cashless.

“For the larger cities, it really made sense to try and keep some cash payment options because it benefited a lot of people,” says Golub, adding that size really matters in terms of the number of riders that are excluded. “In a smaller place, like Eugene, we argued that it didn’t make economic sense to collect fares at all.”

While the cost-benefit analysis and study overall primarily focused on bus ridership, Golub sees bike share and transit as one and the same. After all, if folks have trouble paying for one using a cashless system, then they’ll be unable to access the other. The integration of bike share and transit systems is also a growing trend and in a decade, will hopefully be the norm. Still, it’s hard to say exactly what the future of transit and bike share has in store — what’s important is that we get ahead of equity issues in order to ensure no one is left behind.

“Going cashless is going to harm and exclude some riders,” says Golub. “It’s not going to be a painless transition and agencies should start planning ahead.”

The Better Bike Share Partnership is funded by The JPB Foundation as a collaboration between the City of Philadelphia, the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO) and the PeopleForBikes Foundation to build equitable and replicable bike share systems. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram or sign up for our weekly newsletter. Got a question or a story idea? Email kiran@peopleforbikes.org.