Examining Equity in Accessibility to Bike Share

by Kiran Herbert, Communications Manager

February 8, 2022

A new study from researchers in Hamilton, Ontario, highlights the effect of 12 “equity” stations on traditionally underserved areas.

A woman unlocks a Hamilton Bike Share bike in Hamilton, Ontario. (Copyright Queen’s Printer for Ontario, photo source: Ontario Growth Secretariat, Ministry of Municipal Affairs)

We’ve long advocated for the fact that, when done correctly, public bike share systems can play an important role in making bicycling more accessible to traditionally disadvantaged populations. Unfortunately, many cities introduce shared micromobility with little community engagement, equitable station planning, low-income accommodations, and/or the funding to create a service area that truly serves everyone. For many systems, including Hamilton Bike Share (HBS) in Ontario, Canada, increasing access in underserved neighborhoods has been an iterative process.

In 2017, two years after its system launch, HBS debuted the Everyone Rides Initiative, which provides completely free and heavily discounted bike passes to those in need, with no formal documentation required. The program relies on collaborations with more than 20 community partners and makes accommodations for folks that don’t speak English or who want to pay in cash. There’s also an educational component to the Everyone Rides Initiative with a learn-to-ride class, group rides, and an extended bike safety class.

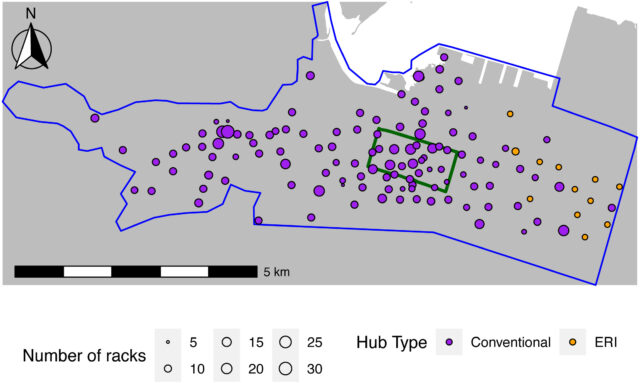

Looking to bring bike share to even more folks, HBS expanded its system footprint to include 12 “equity” stations in 2018. All 12 equity HBS stations are located on Hamilton’s east side and fill in noticeable gaps in the core service area (outlined in blue in the graph below). In a recent case study, researchers investigated the effect of the new stations on accessibility for those living within the core service area. Using various methods (namely a balanced floating catchment area approach) and OpenStreetMap Data, the researchers were able to investigate differentials in people’s access to stations and compare accessibility with and without the equity stations. Walking time thresholds were examined, as was the estimated accessibility according to income groups.

The blue line denotes Hamilton Bike Share’s core service area, with its conventional stations marked in purple and the equity stations in orange.

The findings indicate that the equity stations did indeed increase accessibility for the serviced population at every threshold examined. However, the increase was relatively modest, especially for the population in the bottom 20% of median total household income. The lowest income group was found to have the lowest levels of accessibility, even with equity stations. Researchers concluded that the location and size of the docking stations matters for increasing equity in accessibility.

While more than 118,000 people can access an HBS station within a 15 min walk, that’s still just 85% of the total population in the 40-sq-km core service area (and the core service area is just a small fraction of the larger city). Currently, HBS has some 900 bikes, 130 stations, and more than 26,000 active memberships. From the beginning, however, HBS has acknowledged that considerably more stations (between 380-440) and bikes (around 1,500) were needed to fill in gaps and achieve the recommended station density. The equity stations helped, but only somewhat, and overall did little to resolve inequities in access amongst low-income users. The case study suggests that additional stations are needed to address equity.

Between its Everyone Rides Initiative, educational programming, and intentional expansion, Hamilton has one of the more equitable public bike share systems in North America. Researchers also found that, compared to other cities, the system’s core service area is located in areas with more deprivation. Still, there continue to be disparities in accessibility between income groups. Similarly, other 2019 studies in Tampa, Philadelphia, and Seattle found disparities in station location, annual trips, or access to bicycles, respectively, between levels of income and education.

The team behind the study noted that station size and number of bicycles must be addressed in any equity efforts going forward (in the HBS system, the equity stations had a lower number of racks compared to those in the downtown core). The researchers also identified specific areas in Hamilton for new equity stations that they believe are more likely to increase access for low-income groups.

One of the case study’s final takeaways, however, calls for more community engagement amongst transportation planners and the underrepresented communities they seek to serve. Only by asking folks directly can we know how far they’re willing to walk to reach a bike share station, or where they’d like to see future stations in their neighborhoods. Since this study didn’t examine whether the equity stations increased ridership or resulted in new memberships amongst low-income users, it’s also worth noting that just because a station exists in close proximity, that doesn’t mean folks will use it.

The Better Bike Share Partnership is funded by The JPB Foundation as a collaboration between the City of Philadelphia, the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO) and the PeopleForBikes Foundation to build equitable and replicable bike share systems. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram or sign up for our weekly newsletter. Got a question or a story idea? Email kiran@peopleforbikes.org.