In Philly, $5 bike share memberships for food stamp users take off

by Michael Andersen

August 29, 2016

Photo: Darren Burton.

When your city makes it easy to prove that you qualify for a low-income discount, you’re much more likely to use the discount.

Four months ago last week, Philadelphia become the first city in the United States to test a simple idea: a 67 percent discount on bike sharing memberships for anyone whose income is low enough to qualify for food assistance.

So far, 687 Philadelphians have taken up the offer — enough to make Indego30 Access the fastest-growing bike share discount program in the country. And though some of those memberships have lapsed (just like some of all memberships do) many haven’t. People who signed up for the Indego system this way now account for 10 percent of the system’s monthly membership rolls.

And based on the early statistics, Indego30 Access seems to be terrific at reaching people of color.

People can’t spend their food subsidy on bike rentals, of course, so the ACCESS Card (as electronic benefit transfer cards are known in Pennsylvania) is serving as an ID card only. But simply by letting people use cards they already carry everywhere as their qualifying document for the discount program, Indego has made its signup process dead simple. Unlike almost every other income-based bike-share discount progam, you can sign up online, at any time, on any day.

“You enter your card number and we verify,” said Indego access manager Claudia Setubal. (The system also checks to make sure nobody has created an account with the same card before.) “That’s all you have to do.”

Credit card access is a barrier to bike sharing, but complicated signups may be a bigger one

A Philadelphian at the Indego launch in 2015.

Five years ago, there was a general impression in the brand-new bike-share industry that the most important obstacle to bike share equity was access to credit cards.

After much research on this subject, it’s clear that this is indeed an issue. About 14 percent of Philadelphians, for example, are unbanked.

But it’s also become very clear that credit cards aren’t the only obstacle to equity.

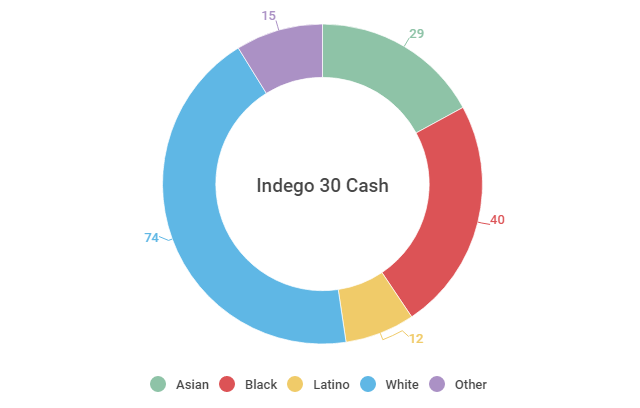

Indego launched in April 2015 with a cash program designed to answer the banking issue. It was among the nation’s first systems to use PayNearMe, which lets people pay cash to add value to their bike share accounts at 7-Eleven or Family Dollar stores. As of July 1, Indego’s cash payment program had at least 170 active members, 56 percent of them people of color:

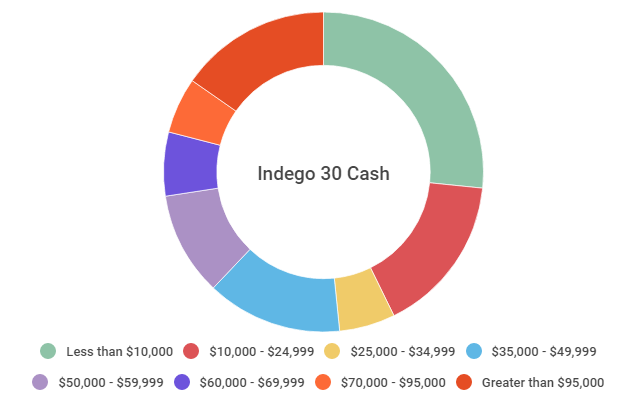

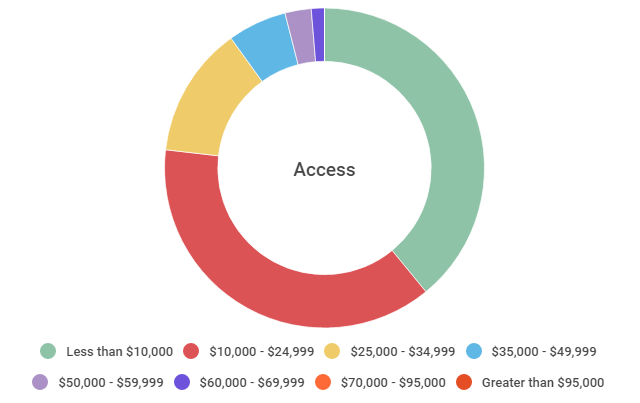

and 43 percent with annual household incomes below $25,000:

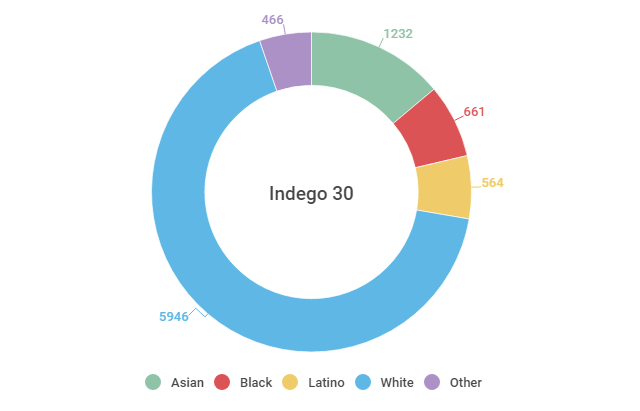

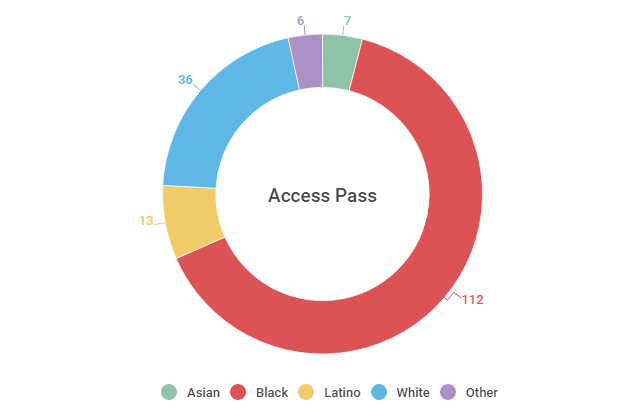

That meant cash-paying members were far more diverse than the “Indego30” monthly members as a whole, by race:

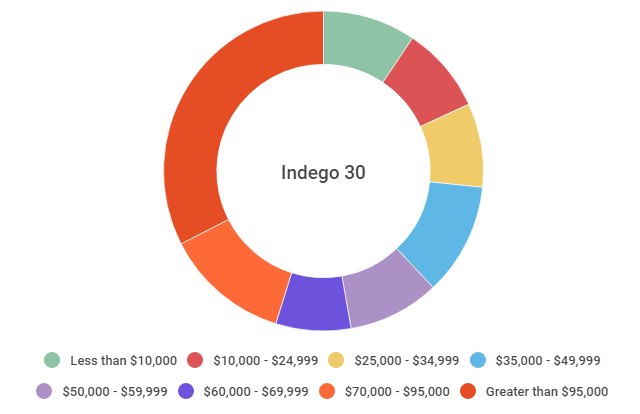

…and by income.

(Thanks to Cassie Owens of Billy Penn, who used Infogram to create these terrific demographic breakdowns. Some people aren’t included because they left demographic questions blank.)

There are also many Philadelphians, though, for whom the barrier isn’t a lack of a credit card. It’s just a lack of money.

Setubal said Indego’s marketing team “knew by the end of the last season that the cash pass by itself wasn’t sufficient” to meet the needs of many Philadelphians who have the most to gain from bike share access. So over the winter of 2015-2016, they started talking about how to create a discount program.

They wanted a program that wouldn’t force people to search for the right phone number, track down obscure paperwork to verify their income or call in during particular hours of operation.

“We were interested in making the enrollment process as simple as possible, since screening processes can be a barrier,” Setubal said.

The big idea came from Naja Killebrew, Indego’s marketing manager. Most low-income Philadelphians, after all, had already proved their income status to the state government and were already walking around with cards in their pockets to prove it. Why not just let people sign up using those cards?

After getting an all-clear from staffers in the state government, that’s exactly what Indego did.

Pricing was designed to encourage recreational trips, too

Some of the ads used to promote Indego, including the new Indego30 Access pass.

Some of the ads used to promote Indego, including the new Indego30 Access pass.

Before rolling out the new discount, Indego asked various Philadelphians in communities they were targeting if it would convince them to sign up, at $5 a month, to get unlimited free bike-share trips of 60 minutes or less.

One thing they heard from some: 60 minutes were well and good for runs to the store or transit station, but the system should be priced to allow for fun and exercise as well.

“People were interested in starting to use it for recreation instead of transportation,” Setubal said. “They would say, ‘I would use it for health and for fitness and to ride with my kids.'”

Based on that, Indego decided that in addition to cutting the membership fee from $15 to $5 per month for Indego Access members, they’d also cut the fee for the second hour of a trip from $4 to $2.

The Indego30 Access program launched April 21, 2016. By July 1, it was already delivering powerful results, diversifying the system by race:

…and by income:

The two programs in combination — cash payment plus an ACCESS Card discount — have been useful too. Out of the 687 accounts created for ACCESS Card holders, 128 (19 percent) were paid with cash.

Indego30 Access isn’t a silver bullet on its own, any more than any program or practice that makes bike sharing useful and appealing to more people. Certainly it’s no substitute for inclusively marketing and designing the system — after all, more black Philadelphians have signed up for Indego30 at the standard $15/month price than there are Indego30 Access members of every racial group combined.

But for people who do happen to have low incomes, discounts can be part of the solution. And when it comes to creating a bike share discount program that low-income people will actually use, Indego is looking, once again, like a national model.

Correction 11:35 am: An earlier version of this post misstated the length of an Indego member’s free trip before fees start to kick in.