Pittsburgh Is Reimagining Mobility

by Kiran Herbert, Communications Manager

January 7, 2022

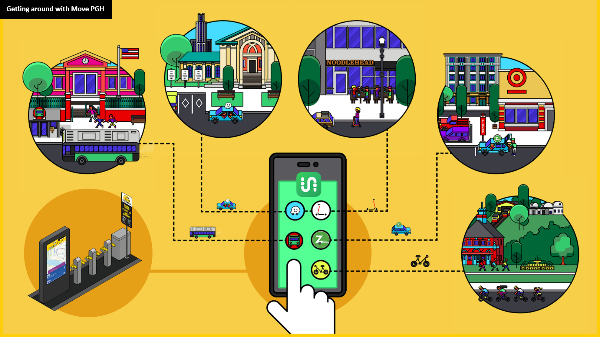

As the first mobility as a service (MaaS) project of its kind in the U.S., Move PGH is making different forms of shared mobility easily accessible — and car ownership obsolete.

One of the new Mobility Hubs in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, launched in 2021 as part of the two-year Move PGH pilot project.

Mobility as a service (MaaS) has gotten a lot of hype in recent years, but with few real-world examples, the concept can seem a bit obscure. The term borrows from Software as a Service (SaaS) — instead of always buying new software and maintaining and owning it, you’re subscribing to a service that a software company continuously updates and improves over time, and allows you to use in multiple ways. When applied to mobility, the idea refers to the integration of various forms of transportation services — transit, bike share, car share, etc. — into a single mobility service accessible on demand.

In the United States, the most extensive MaaS project to date is currently underway in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where the Department of Mobility and Infrastructure (DOMI) is working to make shared mobility more convenient, accessible, and equitable by offering users multiple transportation options through the Transit app and at new Mobility Hubs. Dubbed Move PGH, the two-year pilot program is led by the city, the nonprofit InnovatePGH, and the Pittsburgh Mobility Collective, which includes:

- Port Authority (transit)

- Healthy Ride (bike share)

- Scoobi (moped share)

- Zipcar (car share)

- Waze Carpool

- Spin (scooters)

- Transit (the software)

“The goal is to create a group of mobility options for residents and visitors that make it much easier to get around our city without an automobile,” says David White, executive director at Healthy Ride. “Most of our trips are short distances with a small number of people — we’re trying to respond to the ways people actually need to move around by creating flexible opportunities to use different types of modes.”

For example, once or twice a year a family may need access to a car to visit relatives, go camping, or move some furniture, but most of the year, getting around a city by scooter, bike, shared vehicle, or carpooling makes the most sense. The Move PGH project is about creating easier transportation opportunities with less friction to use. If a resident or visitor can access e-scooters, bikeshare, carshare, public transit, carpooling services, and mopeds all in one app (in this case Transit), then they can easily plan any given journey according to what mode best suits their needs. The more seamless the system, the more individual car ownership loses its appeal.

“What we are trying to demonstrate is that multimodal systems are better together…these things are not in competition,” says Karina Ricks, former director of DOMI, and the brainchild behind the pilot. “What we are in competition with is a built form and a mobility system that relies on private ownership and private operations, principally automobiles.”

In most cities, residents are required to have multiple apps to use different modes — and often, must allow each one to track their data and location. Ricks saw an opportunity for the city to be more prescriptive in its permitting process, thus improving the customer experience. By housing everything in the Transit app and by allowing only one company to operate for each transportation mode, Move PGH is essentially a trial run in putting the user first.

“The single-provider model of each mode is the most innovative thing Pittsburgh is doing,” says White. “In other markets, these companies are competing with each other. But in Pittsburgh, we’ve agreed to collaborate.”

In addition to making it easier on customers, allowing one provider per mode helps incentivize the companies, as well as ensures data sharing, permitting, and connecting everything through one mobile app is an easier process. While the user base of each mode overlap, there aren’t concerns about one mode “stealing” customers from each other, at least not in any significant way. Rather, the modes are designed to complement each other and provide first- and last-mile solutions.

“High ridership on bikes doesn’t mean lower ridership on scooters,” says White. “The easier we make it to not get into an automobile, the more all other modes will benefit.”

Currently, customers can view the availability of all modes in the Transit app — as well as use it to see bus schedules and for route planning — but can only use it to pay for public transportation (folks will be able to use the app to pay for bikes and scooters this spring). The end goal is for every customer to have a single shared wallet available in the Transit app.

Transit was the natural choice as a software provider due to its established presence in Pittsburgh (60,000 people were already using it every month, up to 5 million times), as well as the company’s willingness to collaborate and general commitment to integration. In addition to introducing native integrations into the app between all of the providers, Transit wants to include multimodal transfer discounts (for people switching from bus to bike share, for example), as well as discounted pass bundles.

Having one mobility wallet within the Transit app will also make it easier to subsidize transportation for low-income Pittsburghers. In July 2021, the city launched a Universal Basic Mobility pilot program, which will provide up to 100 low-income residents with access to all of the participating modes of transportation in Move PGH at no cost for six months. Grant funding covers the associated costs, and the Manchester Citizens Corporation has been enlisted to support users with “trip coaching” to ensure they know how to use the various services.

“Transportation mobility is key to economic mobility and a major determinant in household health, education, and welfare,” says Mayor William Peduto. “Universal Basic Mobility, using the services of Move PGH, will demonstrate that when people have a readily available transportation back-up plan they are able to access more opportunities and climb the economic ladder.”

To make things even easier for folks to participate in Move PGH, more than 50 Mobility Hubs are being built throughout Pittsburgh (there are currently 21 in place). To build them, the city worked with Swiftmile, a company that provides charging stations, and Spin to install scooter hubs closer to existing areas of co-located services. The stations, which were tactically installed to connect to city street lights, are branded with Move PGH information and display advertising, transit arrival information, and community announcements. The advertising revenue will help finance the stations and Healthy Ride. The Mobility Hubs surround these stations and will continuously be improved over the term of the pilot. All 50 will include some combination of the following:

To make things even easier for folks to participate in Move PGH, more than 50 Mobility Hubs are being built throughout Pittsburgh (there are currently 21 in place). To build them, the city worked with Swiftmile, a company that provides charging stations, and Spin to install scooter hubs closer to existing areas of co-located services. The stations, which were tactically installed to connect to city street lights, are branded with Move PGH information and display advertising, transit arrival information, and community announcements. The advertising revenue will help finance the stations and Healthy Ride. The Mobility Hubs surround these stations and will continuously be improved over the term of the pilot. All 50 will include some combination of the following:

- Transit stop/station

- Scooter station

- Bike share station

- Car share space

- Moped parking space

- Passenger loading zone

- Greenery

- Furniture

- Public art

The city’s participation in Move PGH was instrumental in coordinating between the utility company, circumventing metering requirements, and acquiring the permits required to connect charging stations to the public grid. Healthy Ride is also building 20 different stations that will connect to the utility grid, allowing its new fleet of electric bikes to charge in public.

“The greatest challenge we face, and other cities face, is coalescing local government or regional and state governments, and layers of city and county and state officials, around a mobility vision or a mobility future,” says White. “Trying new things and iterating off of those things is something our industry does really well and can do quickly. Working with the government takes a lot more time.”

As is the case with any pilot project — despite the substantial time and financial investment from all parties involved, especially Spin — a new administration might decide to end Move PGH. The coalition has also faced a lot of challenges at the state regulatory level and it’s hard to know how things will go after the pilot’s two-year period expires. This, despite the fact that residents have embraced the project (ridership has been phenomenal thus far) and it’s a tangible way to act on both the city’s equity and climate goals. The hope is that Move PGH is able to continue past the pilot, and that other cities step up with funding to piggyback on Pittsburgh’s example.

“If we want to have a future, we need to dramatically change the way people move around. Simply replacing gas-powered vehicles with electric vehicles doesn’t get us where we need to be — it doesn’t solve our climate crisis and it will exacerbate the inequities around mobility in our cities, not alleviate them.” says White. “Cities have to invest in the infrastructure that will encourage people to make trips on lightweight and shared vehicles. I think Pittsburgh has done a good job of doing that so far.”

Learn more about Move PGH through the Shared-Use Mobility Center’s case study on the project — including an in-depth interview with Karina Ricks, who oversaw Move PGH’s implementation.

Does your city have a Universal Basic Mobility program? We’d love to learn more. Email kiran@peopleforbikes.org.