Vision Zero’s Evolving Approach to Equity for All

by Farrah Daniel, Better Bike Share Partnership Writer

December 17, 2019

As the rate of pedestrian fatalities rises, cities have employed a number of traffic safety initiatives to eliminate injuries and fatalities. We recently wrote about one — mandatory helmets — that came as a recommendation from the National Transportation Safety Board.

Vision Zero, on the other hand, has been dubbed the solution to curb the growing trend of traffic deaths in several cities, even though some have seen more accidents leading to fatalities since pledging to the program’s goals.

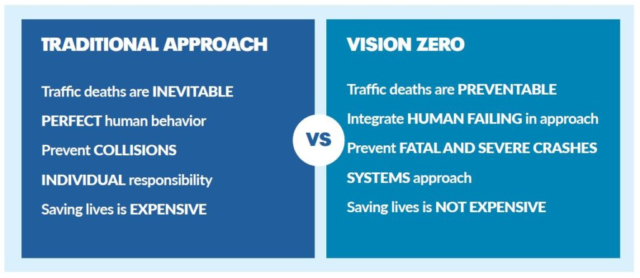

In case you’re unfamiliar with its tenets, Vision Zero is committed to the idea that everyone should be able to move safely in their community and aims to increase safe and equitable mobility for all.

Vision Zero also recognizes that significant reductions in traffic injuries and fatalities are made possible through a shared responsibility between policymakers and system designers. When leaders work together and find equitable ways to improve policies and roadways, commuters gain access to safe and functional systems for travel.

The image below, provided by the Vision Zero Network, briefly summarizes the principles. Notice the acknowledgment of human error? This is an important distinction to make as it affirms that road safety efforts need to be mindful of how to attain results without relying on unrealistic behavior from commuters. Check it out:

What does the implementation look like?

The D.C. Policy Center explains that strategies to prevent traffic fatalities traditionally fall into three categories: engineering, enforcement, and education.

It varies for each city, but these are some examples of how improvements to safety measures are approached:

- New York City, New Orleans and many others have supported the “Complete Streets” policy

- Cincinnati launched a Paint the Streets program

- Philadelphia hosts the annual Philly Free Streets

Jonathan Stafford training community members to become their own advocates.

Washington D.C. is one of a few cities working toward an ambitious goal of reaching zero road user deaths by 2024.

The Washington Area Bicyclist Association’s (WABA) Vision Zero Campaign Coordinator kindly gave BBSP a more in-depth look into his efforts.

For the last two years, Jonathan Stafford has been organizing safety initiatives in two of DC’s communities, Wards 4 and 7, to reduce traffic accidents. His perspective is unique because the projects he both helms and participates in champion micromobility without neglecting the interwoven roles of race and social justice-related issues.

“Understanding how a community uses its current infrastructure and what barriers they face when safe or low-stress corridors aren’t available really helps to prioritize needs and goals,” explained Stafford.

The emphasis on enforcement and the barriers it creates in low income and communities of color, however, remains a shared concern.

At a joint public roundtable last year, Alex Baca, Housing Program Organizer at Greater Greater Washington, argued that Vision Zero’s tactic of enforcement and education through ticketing and fines doesn’t effectively curb dangerous driving behavior, reported Dave Dildine for WTOP.

While the program cites a commitment to centering equity within its principles, enforcement as a solution has statistically reinforced the targeting, racial profiling and hyper-policing of residents in black and brown communities.

Here’s what WABA’s Executive Director Greg Billing said when discussing enforcement as a “last resort tactic” on The Kojo Nnamdi Show:

“If our only mechanism to make a street safer is to go out and have police out there or speed cameras, we’ve already failed at the design of the street. So when you have a community, particularly communities of color, low-income communities where there has been historical disinvestment in safe streets, it’s no wonder that the outcomes of traffic fatalities and serious injuries are higher in those communities. […] [A strategy based on enforcement] is not only going to perpetuate those inequities, but also cause additional harm in those communities.”

To prevent enforcement agencies from targeting underserved and marginalized communities with predatory practices, Deputy Director of Transportation Alternatives Marco Conner believes cities committed to Vision Zero are responsible for these actions:

- Helping enforcement agencies reach a less biased horizon

- Educating officers on the moral significance of focusing on the most dangerous driver behaviors

- Providing anti-racism training and education

- Reaffirming that a specific and articulable danger connected to a specific driver is the only standard for a traffic stop are all necessary first steps

Without addressing the ingrained prejudices, “we will be unable to reach Vision Zero, because all-important traffic enforcement resources will be misdirected, perpetuating linked cycles of racial bias and ineffective traffic enforcement,” writes Conner.

Anacostia River Trail ride w/ community members.

For example, decriminalizing minor offenses like bicycling on the sidewalk would go a long way in addressing racial disparities following arrests, he shares.

While a resolution to unjust enforcement control remains to be found, Stafford does feel hopeful about the journey to zero in DC.

Since becoming a Vision Zero City in 2015, traffic crashes have caused more than 100 deaths in DC, something Stafford thinks is disproportionately affecting people of color and systematically underserved communities.

To provide DC commuters with safer streets through the zero-goal lens, Stafford has spent this year advocating for and bringing awareness to legislation that can affect significant positive change within the city, particularly the Vision Zero Enhancement Omnibus Amendment Act of 2019 — it includes 69 bills that Stafford believes “will really change the way work as related to Vision Zero is done.”

Additionally, progress is well underway with the 20×20 Campaign, an initiative that will supply 20 miles of safe, connected, and equitable protected bike lanes in all four quadrants of DC.

The campaign calls for 25% of the bike lanes to be built in areas of the East River, which are mostly comprised of Wards 7 and 8 and maintain high numbers of black and brown residents.

To note the reflection of WABA’s commitment to equitable transportation outcomes through the campaign, Stafford mentioned he and another WABA colleague will also serve those wards as community organizers.

“Progress looks optimistic right now, primarily because there’s a lot of legislation being done in DC around Vision Zero. Rapid improvements also seem to be happening on the [District Department of Transportation] level, especially ones that heavily affect the most vulnerable roadway users, like bicyclists and pedestrians.”

To learn more about Vision Zero and race as a theme, dive into these articles:

- 9 Components of a Strong Vision Zero Commitment

- A Primer on Vision Zero: Advancing Safe Mobility for All

- Five Ways Vision Zero Should Address Race and Income Injustice

- Racial Inequity in Traffic Enforcement

- Silent Barriers to Bicycling series

- Vision Zero Equity Strategies for Practitioners

- What Happens When a City Tries to End Traffic Deaths

Photos courtesy of Jonathan Stafford.

The Better Bike Share Partnership is funded by The JPB Foundation as a collaborative between the City of Philadelphia, the Bicycle Coalition of Greater Philadelphia, the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO) and the PeopleForBikes Foundation to build equitable and replicable bike share systems. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram or sign up for our weekly newsletter. Story tip? Write farrah@peopleforbikes.org.