Silent barriers to bicycling, part II: Fear of crime among Blacks and Latinos

by Stefani Cox and Charles Brown

February 23, 2017

Source: New Jersey Bicycle and Pedestrian Resource Center.

Welcome back to our series on barriers and incentives to bicycling among Blacks and Latinos. Today we’re looking at fear of robbery and assault, which ranked second only to concerns of traffic safety.

In our first post we gave an overview of the study, which was conducted by Rutgers researchers Charles Brown and James Sinclair. We also talked about why these findings matter for bike share specifically — the individuals studied were largely unaware of bike share, but could potentially benefit from some of the particular features bike share offers.

Let’s take a deeper look at perceptions of crime and how they influence decisions of whether or not to cycle among Blacks and Latinos.

Feeling vulnerable to crime

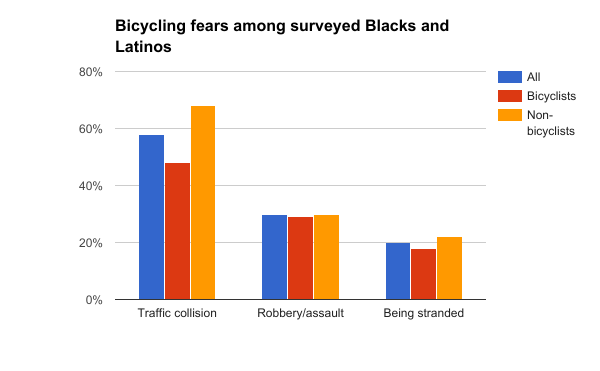

The fear of robbery and assault among Blacks and Latinos held true for both people who already biked and those who were weighing whether they would bike in the future. Additionally, one in five of the Blacks and Latinos surveyed said they were concerned about being stranded somewhere while using a bicycle.

The focus groups gave more context to the survey responses. In the Black focus group, crime fears seemed to center on the worry of having one’s bicycle stolen, whereas the Latino group maintained more fear of being a physical target of crime while bicycling through perceived high-crime neighborhoods.

Brown and Sinclair did some further research to deepen their understanding of where the surveyed individuals lived and what those environments were like. They found underlying trends that explained some of the fears. The majority of respondents lived in major urban centers that collectively were the source of 39 percent of all of New Jersey’s violent crime. These areas saw comparatively high rates of murder, purse snatching, highway robberies, and bicycle theft.

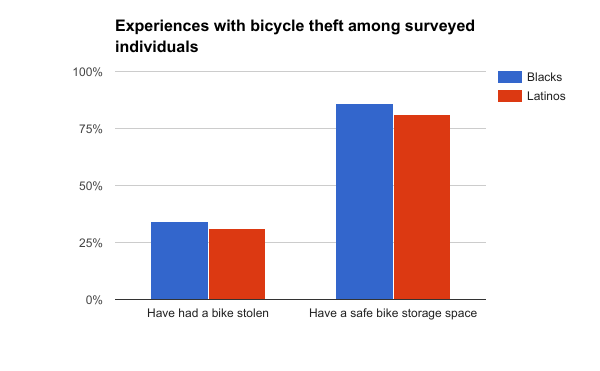

In fact, many respondents had personal experiences with bicycle thefts. Nearly one out of every three respondents reported being victims of bike theft in the past, with many having been victimized multiple times. Blacks reported having had their bikes stolen slightly more often than Latinos, however, Latinos were slightly less likely to have a safe storage place for their bike in comparison to Blacks.

Connecting fear of crime to transportation planning

After taking a look at what is going on for some Blacks and Latinos when it comes to perception of crime and bicycling, it’s important to think through what that means for transportation planning.

In discussing issues of crime, it’s critical not to promote policies or strategies that would make such neighborhoods more hostile places. Thus, the solution is not to ramp up policing in urban neighborhoods. (In our next article, we’ll cover fear of racial profiling.)

To the contrary, Brown states in a recent ITE Journal article,* “Since ‘crime prevention is everybody’s business,’ the personal safety of Black and Hispanic cyclists can no longer be ignored or dismissed by transportation professionals as simply a police issue.” Rather, the key might be deeper and more meaningful engagement of communities of color.

Brown argues that existing inequalities mean that Blacks and Latinos often don’t have the power to get crime issues substantively addressed during planning processes. In fact, such groups often have a hard time even getting a seat at the planning table. Moving forward, Brown explains, “Decisions cannot be made in a bubble or outside the social context and realities of these communities.”

He also suggests that transportation professionals should be looking at crash statistics and crime statistics together in order to understand which corridors are perceived as dangerous. Armed with better knowledge, such professionals can use built environment techniques to make certain places feel safer from crime, much in the same way design strategies are employed to prevent traffic fatalities.

Brown says that without understanding which areas are perceived as unsafe and why, transportation professionals will have a difficult time achieving citywide goals of reducing congestion and pollution through increasing biking. Taking into account the “silent” social factors behind bicycling matter too.

Bike share experts in particular should pay attention to the findings Brown and Sinclair unearthed, since fixed bike share stations could provide at least a partial answer to the fear of bicycle theft. However, station siting could be a concern if individuals feel stranded or unsafe at the station location.

Up Next

In the coming weeks we’ll discuss how concerns over racial profiling affect bicycling among Blacks and Latinos, as well as dive into the big topic of traffic safety.

In case you missed it, here are the additional posts in our series:

>Silent barriers to bicycling, part I: Exploring Black and Latino bicycling experiences

>Silent barriers to bicycling, part III: Racial profiling of the Black and Latino community

>Silent barriers to bicycling, part IV: Infrastructure in Black and Latino neighborhoods

*Please note that the data used in our blog series comes from Brown’s 2017 Transportation Research Board poster, not from the related ITE Journal article.

This post was written by Stefani Cox, MCP, Equity Writer at PeopleForBikes and edited by Charles Brown, MPA, Senior Researcher and Adjunct Professor at Rutgers University.

The Better Bike Share Partnership is a JPB Foundation-funded collaboration between the City of Philadelphia, the Bicycle Coalition of Greater Philadelphia, the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO) and the PeopleForBikes Foundation to build equitable and replicable bike share systems. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram or sign up for our weekly newsletter. Story tip? Write stefani@peopleforbikes.org.