How much does each bike share ride cost a system? Let’s do the math

by Michael Andersen

August 16, 2016

It’s cheap to operate. But how cheap? Equitable bike sharing depends on the answer.

Nobody knows quite how low the price of a bike share trip can go.

Compared to a daily bus rider, a daily bike share rider with a monthly or annual pass pays very little per trip. Still, many people struggle to justify bike share memberships, especially if they don’t use the system daily — after all, bike sharing is often an add-on to public transit rather than a primary mode that can actually get you out of a transit pass or a car payment.

That’s why discount programs for low-income people are important. Last week, we reported on the nation’s most popular discount: Half of all Chicagoans qualify for an introductory $5-per-year Divvy Bikes membership, and 1,450 Chicagoans took advantage in the last 12 months.

The Chicago Department of Transportation decided that if it offered the $5 per year indefinitely, it’d lose too much money. So after getting the first year at $5, a Divvy for Everyone member sees the rate rise to $50 per year (or $5 per month), then to the full $99 per year (or $10 per month) in year three.

Fair enough, but we still wanted to know: How much money does a bike share system lose on each $5 annual membership it sells?

The average cost of each additional bike share trip would be a very useful number to know

A Divvy Bikes station. Photo: Steven Vance.

If a public bike share system were a private business, this would be one of its most important statistics: the marginal cost per transaction. In most cases, that’s the price floor for a business’s discount offers. Charge less than your marginal cost and you start to lose money on each sale. The marginal cost per transaction is the invisible price point where the experience of getting a new customer flips from “every transaction helps” to “some transactions help but some don’t.”

Public bike share systems aren’t private businesses, so they should value more than just profitability. But the marginal cost per transaction still matters, because it’s one way to calculate how low a system’s base fare can get — and also how much subsidy a fare-discount program like Divvy’s will require.

Trouble is, nobody has ever tried to publicly figure out what this number is for a U.S. bike share system.

At first, it might seem as if each ride would cost the system nothing. After all, the bikes and stations are already sitting there. But bike share trips do actually create some additional costs:

• Most importantly, there’s a certain probability that a given trip will remove the final bike from a popular station, forcing a staffer to show up with a truck of bikes to refill (“rebalance”) the empty station. Rebalancing is the single largest operating expense for most bike share systems.

• There’s a certain probability that a trip will involve a customer service phone call.

• There’s a certain probability that a trip will give the bike or its station a bit more wear and tear than it’d get by just sitting unused.

• There’s a fee with every credit card transaction.

How it all adds up

A Hubway station in Boston.

It’s possible for a bike share operator to estimate its marginal cost per trip. But many systems haven’t done so publicly, let alone tried to figure out a national average.

Over the last two weeks, BetterBikeShare.org contacted 11 bike share experts from around the country to ask if they’d ever seen an estimate like this. (We asked Sean Wiedel and Amanda Woodall of the City of Chicago; Steve Hoyt-McBeth of the City of Portland; Mitch Vars of Nice Ride Minnesota; Brodie Hylton of Bicycle Transit Systems; Nick Bohnencamp of Denver B-Cycle; Ben Bolte of GREENbike in Salt Lake City; Paul DeMaio of Metrobike LLC; Susan Shaheen of the Transportation Sustainability Research Center at UC Berkeley; Phil Goff of Alta Planning + Design; and Jennifer Toole of Toole Design Group.) None said they had.

So at the advice of Hoyt-McBeth, who recently launched Portland’s BIKETOWN system and who sits on the National Bike Share Association board, we focused specifically on Denver B-Cycle, a relatively long-running nonprofit system that publishes unusually detailed annual reports.

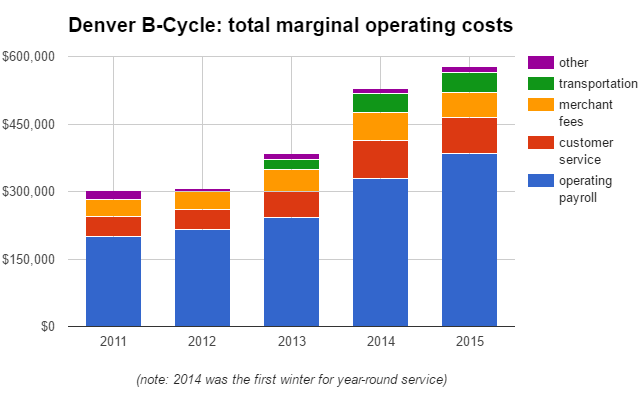

We were interested only in the budget line items that would seem to scale up and down based on the number of rides in the system. At Bohnencamp’s advice, we included operating (but not general/administrative) payroll; customer service and call-center time; merchant fees; transportation expenses; and “other” operating expenses. Also we left off the system’s first year, 2010, because we figured it’d be unusual.

Customer service/call center fees aren’t broken out in the annual reports, so we took Bohnencamp’s ballpark estimate for those costs in 2015 ($80,000) and scaled it backwards in time in proportion to the number of trips.

Here’s the data. And here’s what it looks like:

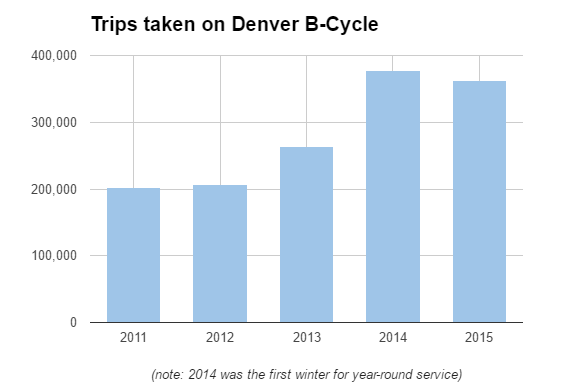

Denver B-Cycle costs have gone up a lot over the years! But so has its usage:

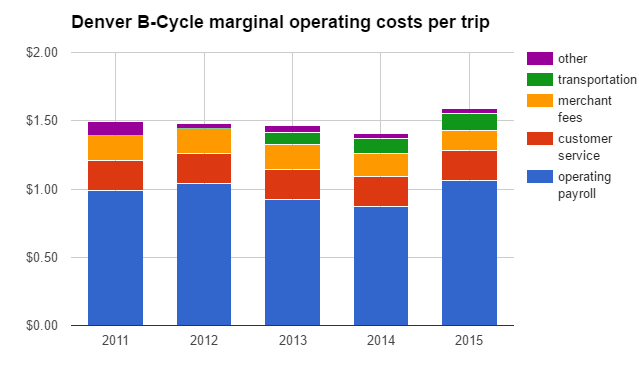

So let’s divide the one by the other to get our estimate of the costs associated with each trip:

Pretty stable. It seems fairly safe to estimate that in Denver, the average additional bike-share trip adds about $1.50 to the system’s costs.

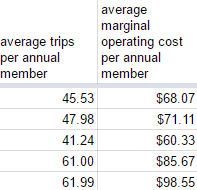

Let’s make one last calculation: how much does that add up to per member per year?

B-Cycle offers those numbers, too: it tells us how many trips the average annual member took each year. Multiply that by the average marginal cost per trip and you get the marginal cost per member:

Of course, these figures vary widely by member, and it’s also a safe guess that the average person in Denver B-Cycle’s subsidized membership program ($10 per year) rides less frequently than the average person who’s found it worthwhile to pay the full $135 per year — it doesn’t take many bike share trips to justify a $10 purchase. But these figures start to offer a sense of what it “costs” Denver B-Cycle to subsidize some of its members.

Keep in mind that these figures apply only to Denver. Bohnenkamp, executive director of Denver Bike Sharing, said that other systems’ marginal costs probably vary widely, though other systems could use a similar process to estimate theirs.

Offering low-price memberships to lower-income people remains a good idea

Yes, it costs money to sell some bike share memberships for less than their cost — just like it costs money for grocery stores to offer big coupons for newly stocked products or public transit agencies to offer discounts to people with disabilities.

Sometimes it’s good business. Other times it’s just good government.

“Transit’s purpose is to serve everyone and some population groups need more assistance to become a customer of the service,” said Paul DeMaio, a bike share consultant who manages Capital Bikeshare’s northern Virginia service. Chicago, he said, “is certainly benefiting from more trips and improved public health” thanks to Divvy for Everyone.

Discounting some memberships can also be a way to boost system revenue long-term, said Brodie Hylton, vice president for marketing at bike share operator Bicycle Transit Systems.

“Since the bike is being ridden, there is marketing benefit to seeing a bike in use,” he said in an email, adding: “I would say there is marginal benefit of bikes being used up to a certain point of utility, and particularly if bikes are being ridden to a station with high demand (reverse commute), or if bikes are underutilized (less than 3 rides per day). It’s not rocket science, but it’s complicated.”

The Better Bike Share Partnership is a JPB Foundation-funded collaboration between the City of Philadelphia, the Bicycle Coalition of Greater Philadelphia, the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO) and the PeopleForBikes Foundation to build equitable and replicable bike share systems. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram or sign up for our weekly newsletter. Story tip? Write info@betterbikeshare.org.