Barriers to Bike and E-Scooter Use in Black Communities

by Kiran Herbert, Communications Manager

March 28, 2023

The Arrested Mobility report is the result of an investigative survey of bicycle, pedestrian, and e-scooter policies across all 50 U.S. states.

Mobility is an essential component of our daily lives — it’s how we move around to access jobs, schooling, healthcare, or any of our other fundamental needs. But for Americans that are Black, Indigenous, or people of color (BIPOC), mobility is often “arrested” due to institutionalized structural racism in policy, planning, design, infrastructure, and law enforcement. In the last few years alone, we’ve seen how “routine” traffic stops can turn deadly for Black drivers, a phenomenon that also extends to traveling by foot, bicycle, or e-scooter.

“If you are Black, you could get harassed, arrested, jailed overnight, brutalized and worse, simply for crossing the street, cycling, or using an e-scooter,” says Charles T. Brown, founder and CEO of Equitable Cities, which recently released a new study on this topic. “Police often weaponize the vague, archaic, and unequally enforced laws that govern pedestrian, bike, and e-scooters in all 50 states.”

The report, titled “Arrested Mobility,” shows how these policies aren’t just propped up by a small number of bad actors but rather are enshrined in state, local, and county laws in the two largest cities in every state. In addition to the obvious trauma that can make even the most essential trip to the grocery store a fraught affair, these transportation policies limit mobility, opportunity, and access for BIPOC. They also have implications beyond mobility, contributing to adverse social, political, economic, environmental, and health outcomes.

What’s less often discussed in the media is how rates of car ownership are lower for Black households yet Black people are also substantially less likely to get around by walking and biking than white people (they’re significantly more likely to take transit, representing 24%

What’s less often discussed in the media is how rates of car ownership are lower for Black households yet Black people are also substantially less likely to get around by walking and biking than white people (they’re significantly more likely to take transit, representing 24%

of all transit riders, almost double their proportion of the national population). For this population, active transportation could present an incredible opportunity to be mobile without needing to rely on a car or transit. As the report shows in firsthand interviews and an incredible amount of data though, there are larger structural forces at play.

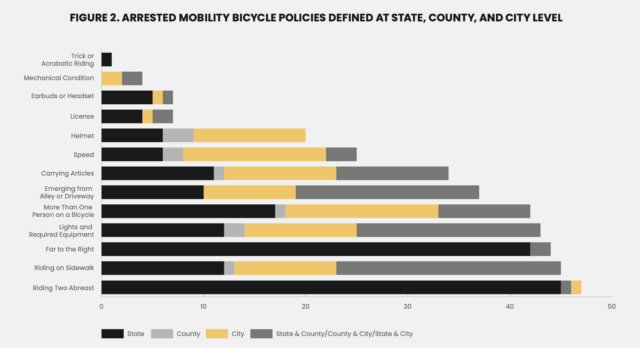

Many of these laws were created to serve a safety purpose. These include bike laws that pertain to riding behavior, licensing, or helmet and light laws, as well as e-scooter laws that regulate parking and speed limits. For example, the report found that a whopping 64% of states have laws prohibiting the operation of bikes on sidewalks, even when the roads that run alongside them lack safe infrastructure and are objectively too dangerous to bike on (these types of roads are also disproportionately common in Black neighborhoods). At the city level, the laws are even more troubling and offer police officers wide discretion. In day-to-day life, many of these laws are enforced inequitably, serving as a legal mechanism for discriminatory, racist, and predatory police enforcement.

“Black people understand that safety may have been at the root of laws governing mobility but they also know that these laws are frequently applied to them far disproportionately than white people moving about their daily lives,” says Brown, adding that many of these laws are outdated and do nothing to make people on our streets healthier or safer.

Brown and the two other researchers involved in the study found five characteristics associated with racial discrimination in enforcement across the U.S.:

- Research shows discriminatory or inequitable enforcement

- Ongoing advocacy efforts that speak to the discriminatory enforcement of policies

- Highly subjective and confusing laws and policies

- Laws that are almost impossible to enforce equitably

- Absence of evidence, or inconclusive evidence, that policies improve safety outcomes

The researchers’ aim isn’t to determine the extent to which certain policies are used in a racially discriminatory fashion but rather to supplement the efforts of activists by documenting the types of laws related to walking, cycling, and e-scooter use in their entirety. Additionally, the research team identified factors that may contribute to these laws being used in a racially discriminatory manner. By documenting injustice, the Arrested Mobility report highlights the importance of a multisectoral approach to increasing BIPOC access to active transportation, their use of it, and their safety while doing so. It also provides a jumping-off point for additional research.

The report is comprehensive, complete with background information, policy scans according to mode, an appendix that organizes unjust laws according to state, and six resulting recommendations for advocates, researchers, and policymakers. The recommendations are as follows:

- 1. Repeal laws, decriminalize violations, and promote alternative enforcement for policies that have minimal impact on safety and that are enforced in a racially discriminatory manner.

- 2. Embrace pedestrian, bike, and e-scooter infrastructure as a tool to reduce unwanted encounters with police, promote safety, and encourage mobility.

- 3. Reduce and/or eliminate court fines and fees associated with pedestrian, bicycle, and e-scooter policies (The places where Black Americans live are often more reliant on fines and fees as revenue sources, but Black Americans struggle disproportionately to pay these fees.).

- 4. Place limits on pretextual traffic stops, in which police use minor violations as a justification to investigate unrelated crimes without a warrant.

- 5. Engage the bicycling industry in a conversation about the feasibility of manufacturing and selling bikes with front and rear lamps included, as is mandated in several jurisdictions.

- 6. Better understand the scope of arrested mobility:

A. Generate additional research to create comprehensive inventories of enforcement of pedestrian, cycling, and e-scooter policies at the local, county, state, and federal level.

B. Expand research on arrested mobility in other modes of transportation, such as public transit, air travel, and travel by automobile, as well as planning policies and polity.

C. Mandate greater transparency and access to data on the enforcement of laws related to walking, biking, and using e-scooters. Many police departments do not gather data on the race of people who are stopped, this should be required.

It’s hard to read the report and not feel angry at the injustice Black Americans specifically, and other people of color more generally, have to undergo every single day. Not only is this population more likely to be injured or killed while engaging in transportation (or have an unpleasant, unwarranted interaction with the police), but the trickle-down effects are even worse and harder to measure due to the unequal access to critical resources, jobs, education, and healthcare that accompanies arrested development.

As this study makes clear, there’s an urgent need for more research at the local level, as well as a widespread reform in our laws and policing policies. What this report doesn’t touch on but alludes to in its conclusion, is the fact that many of these laws are compounded by city planning policies and polity, which work in different ways to further restrict the movement of BIPOC through public space. Mobility is a basic human right — it’s time we start acting like it.

“Arrested Mobility: Barriers to Walking, Biking, and E-Scooter Use in Black Communities in the United States” is available for download here.

The Better Bike Share Partnership is funded by The JPB Foundation as a collaboration between the City of Philadelphia, the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO), and the PeopleForBikes Foundation to build equitable and replicable bike share systems. Follow us on LinkedIn, Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram or sign up for our weekly newsletter. Got a question or a story idea? Email kiran@peopleforbikes.org.