New Haven 6th graders help plan bike share system they’ll use someday

by Stefani Cox

June 23, 2017

Source: Krysia Solheim.

In New Haven, one schoolteacher’s class project led to a whole new approach to community participation in bike share station siting.

Doug Hausladen, director of the New Haven Department of Transportation, Traffic, and Parking, along with Krysia Solheim, owner of consulting firm Viosimo LLC, initially embarked on a bike share rollout process with a traditional public meeting structure. The result, they said, was that they saw the usual planning meeting crowd, but not many new faces. In a place as diverse as New Haven, they couldn’t help but wonder if they were really reaching a full cross section of the community.

New Haven builds planning activity with youth

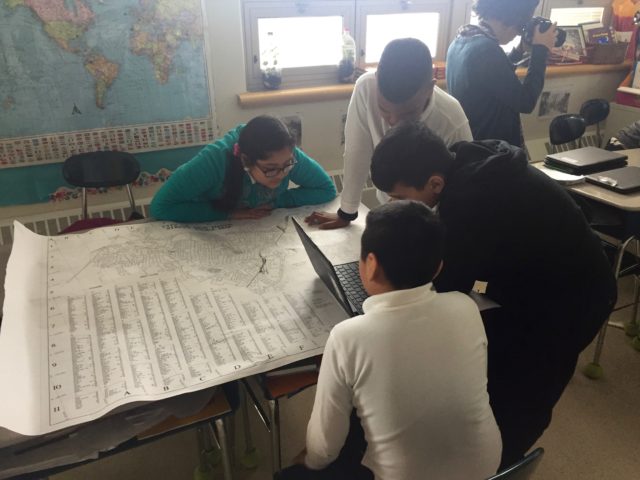

Then Hausladen and Solheim were approached by a local teacher named David Weinreb, who invited them to do a bike share activity with his sixth grade students. This lead the planners to do an interactive planning and visioning session at Fair Haven School in Weinreb’s classroom, where most of the students come from recently-immigrated families.

During the bike share activity, Solheim started with a PowerPoint presentation on climate change, but quickly turned the session over to the students. She assigned them to the task of deciding how to develop more sustainable transportation options for New Haven, as well as to finding the 10 best locations for bike share stations as a class.

Students were thoughtful in considering the factors that would make for a good bike share station, such as putting them close to parks, nursing homes, or places where whole families could use them. The students used Google Maps to help pinpoint specific locations, and then marked them on a physical map for everybody to see. The class had to discuss any differences of opinion as a group until there was consensus.

Here’s the final map they came up with:

Source: New Haven Independent.

The outcome of the activity seems to have been quite positive all around.

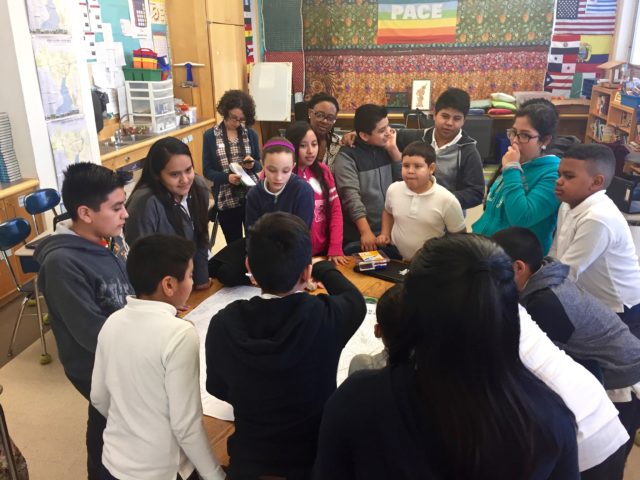

“I’m thrilled the city is including the essential perspectives of new young immigrants,” says Weinreb. “My students relish the opportunity to brainstorm around the challenges they and their families face and to propose creative solutions. Our community and our city is enriched by their voices. The more our students experience this, the stronger our city becomes.”

School project inspires citywide planning process

Source: Krysia Solheim.

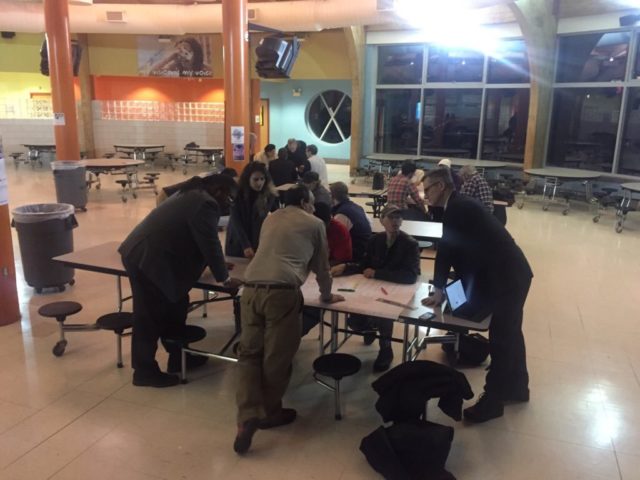

The activity planning sparked a new approach for their public meetings as well. “We had received feedback on public meetings,” says Hausladen. “People wanted more engagement. They wanted to get their hands dirty.”

At the second public meeting, Hausladen and Solheim had attendees break up into groups and collectively recommend 30 locations for bike share stations to go. They used the presence of local resources as a large factor in choosing locations, such as existing bike lanes, schools, and other places they would frequent.

The city then brought the suggestions into the goNewHavengo website, so that they were publicly available. Residents can go to the website and suggest additional locations, as well as see what stations have already been proposed.

“All of these locations that people were recommending, we had them put into the 311 platform so they were visible to everyone,” says Solheim. “People could put in suggestions individually, or email, or call, or use another public outreach forum.”

New Haven was also conscious of involving local partners, such as the community foundation, university system, housing authority, and board of education, in making decisions about the RFP to select a bike share operator.

“We crowd-sourced using a Google Doc,” says Hausladen. “The review process was community-oriented.”

Communication is critical to success

Source: Krysia Solheim.

The difficult part about this kind of community process is that not all of the suggestions received can be turned into stations, at least not right away. The planners made sure to communicate that fact to the sixth graders and other residents they engaged with as early and clearly as possible.

Still, Solheim and Hausladen hope that the participatory process will lead to more community ownership (as opposed to simple community input) over the new bike share system. They developed a weighted model to evaluate the various suggestions through data analysis, including factors such as population density, jobs density, access to transit, and proximity to schools, hospitals, and libraries.

In getting a participatory planning process like this going, it helps to have an active community leader, like Weinreb, say Solheim and Hausladen. And it doesn’t hurt either, they say, that New Haven has an “extremely engaged” mayor in Toni Harp.

All in all, their work seems to suggest that planners should never overlook youth as a key voice in decision-making.

“It can’t be overstated that if you actually want to know what’s going on in your community ask a 12-year-old,” says Hausladen. “They’re like sponges, seeing everything and absorbing everything.”

The Better Bike Share Partnership is a JPB Foundation-funded collaboration between the City of Philadelphia, the Bicycle Coalition of Greater Philadelphia, the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO) and the PeopleForBikes Foundation to build equitable and replicable bike share systems. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram or sign up for our weekly newsletter. Story tip? Write stefani@peopleforbikes.org.