The wealth gap is even worse than the income gap – and bike sharing can narrow both

by Michael Andersen

October 25, 2016

Lori Lematta, second from right in white, at a bike sharing class in her old apartment building. Photos: BBSP.

If you want to understand how abruptly poverty can change a life, and how bicycles can help it slowly change back, talk to Lori Lematta.

I met her sitting quietly against the wall of the little common room on the second floor of Alder House Apartments in downtown Portland. A young man from a nonprofit bike shop was rattling through a list of tips for riding a bicycle.

“It’s been at least 20 years since I actually rode,” Lematta, 52, told me a little nervously.

Earlier in her life, riding a bike had felt like entertainment. Then, suddenly, it became an out-of-reach luxury. In 2010, Lematta’s struggle with addiction combined with a health issue, a layoff and finally a fire in her house. Yanked from every angle at once, her life twisted apart.

The first night she’d been homeless, Lematta said, she didn’t know where to go.

“I had no idea how to be homeless,” she recalled. “I had no idea about social services.”

So she just started walking in circles through the streets.

“I found a neighborhood near where I lived and I walked around all night because it was the safest thing I could think of to do — I just walked around with my dog,” she said. “That went on for a week and then I found a shelter.”

In the months that followed, a decent bicycle could have kept Lematta mobile — able to make it to appointments, apply for work, build new friendships. But having $200 in the bank all at once, enough to buy one, had become the least of her worries. These days, after years of work to reassemble her life, she lives on $150 a month by selling Portland’s street paper (she gets 75 cents per issue sold) and stays afloat with food benefits and a Section 8 housing voucher. Alcohol-free since 2013, Lematta also volunteers teaching visual art skills to other people dealing with addiction and mental health issues, aiming for a career in that field.

Through all of it, until last month, she’s had one form of transportation: her feet.

“For 10 years now, I’ve been hoofing it,” Lematta said. “It’s depressing. It’s hard on my bursitis.”

But she simply hasn’t had another option. A car is out of the question. Transit costs $2.50 a ride or $100 for a monthly pass.

“I do have a bank account, but sometimes it only has $2 to $3 in it after I pay rent,” she said.

That’s where bike sharing has come in to Lematta’s life.

Even more than income inequality, bike sharing is a response to wealth inequality

Lematta is among millions of Americans who have faced what some people call a “poverty trap.” Without more money, it’s hard to be mobile. Without more mobility, it’s hard to get more money.

Her income is low. But that’s not her whole money problem. In fact, it might not even be her most important one. When her disaster hit, Lematta was on the losing side of an even deeper problem in the United States than income inequality: wealth inequality.

Half of Americans say they’d struggle to find $400 in an emergency. There’s a familiar term for this: living paycheck to paycheck.

For people who aren’t lucky enough to be able to borrow from friends or family in a pinch, living paycheck to paycheck is the way that a transmission failure can lead to job loss, or a burst appendix can lead to eviction.

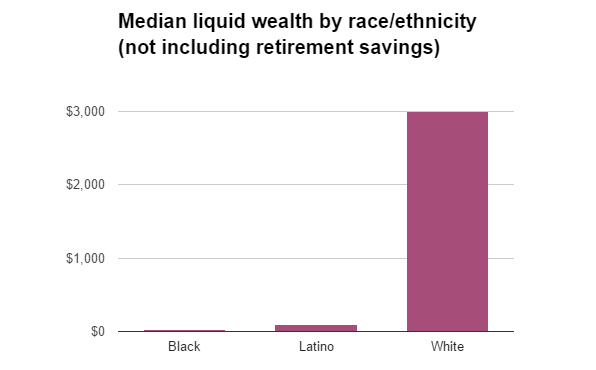

Depending on your race, you can be at even more risk. Thanks in part to generations of housing discrimination, black and Latino Americans tend to have dramatically less liquid wealth than white and Asian Americans. According to a Center for Global Policy Solutions analysis of 2011 U.S. Census figures, aside from retirement accounts, half of all black-led households have less than $25 in liquid wealth at any given time.

Source: Rebecca Tippett’s calculations from 2011 Census data.

And whatever race you happen to be, if you’ve got very little money on hand at any given time, it’s hard to deal with unexpected disasters in your life and escape a poverty trap like Lematta’s was.

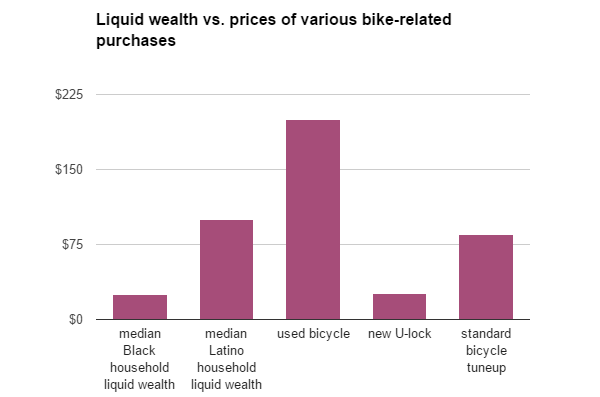

For example, a decent used bicycle might save you money or help you get or keep a job. But for many, it simply costs too much money.

Bicycle price: BicycleBlueBook.com. U-lock price: Amazon. Tuneup price: Trace Bikes and Bike Gallery.

Measured against centuries of inequality (racial and otherwise), the price of a bicycle might seem trivial. But in circumstances like Lematta’s — especially in those crucial weeks and months after her 2010 catastrophe, trying to thread her life back together — a decent bicycle can make a major difference.

Without enough money to fall back on, Lematta said, “once you get down, it’s really hard to get up.”

One of the most important ways bike sharing can address poverty is that it can make it a little easier for people to get back up.

A permanent cure for flat tires and worn brakes

Lematta had heard about the bike sharing workshop from her friend Heather.

Heather Morrill is a program staffer for The Giving Tree, a Portland nonprofit that connects people in buildings like Alder House Apartments with public services and things to do. She and Lematta had met when Lematta lived in the building.

Morrill had heard about the discount bike share memberhsips available to low-income Portlanders and realized that they could be a big help to many people she knew at Alder House. Among the building’s 131 single-room units, Morrill estimated, fewer than a dozen residents owned cars, but maybe 35 owned some sort of bicycle.

“How many of those are operable is a different question,” Morrill added.

But as Morrill realized, the low-rent building was now in the middle of one of the densest clusters of bike sharing in the country, with 19 stations per square mile.

For people in the area, bike sharing would mean no squeezing bikes into elevators or stairwells. No flats. No brake repairs. No need to save for months if their bike was stolen.

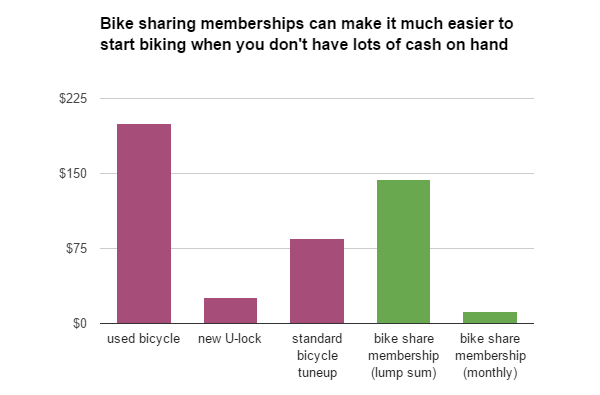

Just $12 a month. Or with the income discount, $3 a month.

I asked Lematta if she’d consider bike share membership if she had to pay $100 once a year. Not a chance, she said: she never has that much cash to spare. I asked if she’d sign up at $3 or $12 a month.

Maybe, she said. If it was useful.

‘All it takes is five minutes and my whole mind has switched over’

Biketown users on Portland’s riverfront.

I’d met Lematta in August. Last Tuesday, we spoke again.

She was brimming with enthusiasm about the bike sharing program.

“At this point in my life, I’m trying very, very hard to get my life together,” she said. “I discovered just a little bit of bicycle riding really helps my depression.”

Being unable to leave the heart of a city is emotionally exhausting, Lematta said, and being able to leave it whenever she wants, for the first time in years, is thrilling.

“It kind of knocks you down to be constantly bombarded by people and noise and concrete — it drives you crazy,” she said. “Being on a bicycle, it’s like being a kid again. … All it takes is five minutes and my whole mind has switched over. It’s really bizarre.”

It’s not just the mobility, she told me. It’s “the good it feels to do things that so-called normal people can do.”

Lematta’s income hasn’t changed in the last two months, and neither has her wealth. But her life feels a lot richer already.

“I haven’t done it yet, but I think the best thing that’s going to happen to me is going to be riding along the waterfront,” she said. “That’ll be my vacation.”

Correction 10/27: An earlier version of this post overstated the monthly fee for Portland’s discount program.

The Better Bike Share Partnership is a JPB Foundation-funded collaboration between the City of Philadelphia, the Bicycle Coalition of Greater Philadelphia, the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO) and the PeopleForBikes Foundation to build equitable and replicable bike share systems. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram or sign up for our weekly newsletter. Story tip? Write info@betterbikeshare.org.